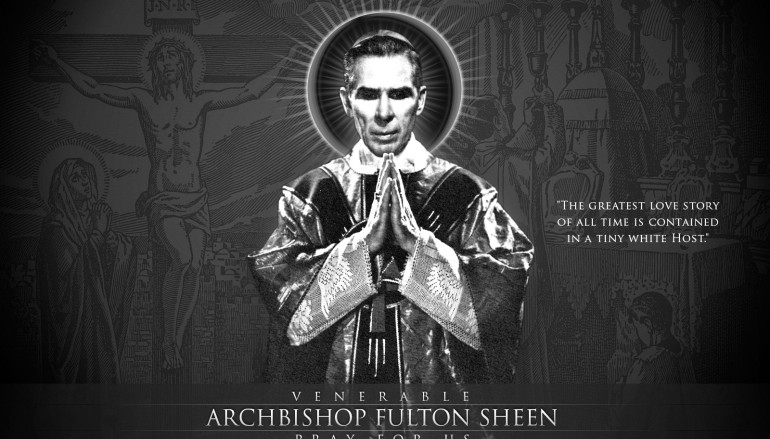

Part One – Calvary and the Mass – The Confiteor

PART ONE – THE CONFITEOR

by Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, Ph.D., D.D., LL.D., Litt.D.

” Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.”-Luke 23:34.

The Mass begins with the Confiteor. The Confiteor is a prayer in which we confess our sins and ask the Blessed Mother and the saints to intercede to God for our forgiveness, for only the clean of heart can see God. Our Blessed Lord too begins His Mass with the Confiteor. But His Confiteor differs from ours in this: He has no sins to confess. He is God and therefore is sinless. “Which of you shall convince me of sin?” His Confiteor then cannot be a prayer for the forgiveness of His sins; but it can be a prayer for the forgiveness of our sins. Others would have screamed, cursed, wrestled, as the nails pierced their hands and feet. But no vindictiveness finds place in the Savior’s breast; no appeal comes from His lips for vengeance on His murderers; He breathes no prayer for strength to bear His pain. Incarnate Love forgets injury, forgets pain, and in that moment of concentrated agony reveals something of the height, the depth, and the breadth of the wonderful love of God, as He says His Confiteor: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

He did not say “Forgive Me,” but “Forgive them.” The moment of death was certainly the one most likely to produce confession of sin, for conscience in the last solemn hours does assert its authority; and yet not a single sigh of penitence escaped His lips. He was associated with sinners, but never associated with sin. In death as well as life, He was unconscious of a single unfulfilled duty to His heavenly Father. And why? Because a sinless Man is not just a man; He is more than mere man. He is sinless, because He is God-and there is the difference. We draw our prayers from the depths of our consciousness of sin: He drew His silence from His own intrinsic sinlessness. That one word “Forgive” proves Him to be the Son of God.

Notice the grounds on which He asked His heavenly Father to forgive us-“Because they know not what they do.” When anyone injures us, or blames us wrongly, we say: “They should have known better.” But when we sin against God, He finds an excuse for forgiveness our ignorance. There is no redemption for the fallen angels. The blood drops that fell from the cross on Good Friday in that Mass of Christ did not touch the spirits of the fallen angels. Why? Because they knew what they were doing? They saw all the consequences of their acts, just as clearly as we see that two and two make four, or that a thing cannot exist and not exist at the same time. Truths of this kind when understood cannot be taken back; they are irrevocable and eternal. Hence when they decided to rebel against Almighty God, there was no taking back the decision. They knew what they were doing! But with us it is different. We do not see the consequences of our acts as clearly as the angels; we are weaker, we are ignorant.

But if we did know that every sin of pride wove a crown of thorns for the head of Christ; if we knew that every contradiction of His divine command made for Him the sign of contradiction, the Cross; if we knew that every grasping avaricious act nailed His hands, and every journey into the byways of sin dug His feet; if we knew how good God is and still went on sinning, we would never be saved. It is only our ignorance of the infinite love of the Sacred Heart that brings us within the hearing of His Confiteor from the Cross: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

These words, let it be deeply graven on our souls, do not constitute an excuse for continued sin, but a motive for contrition and penance. Forgiveness is not a denial of sin. Our Lord does not deny the horrible fact of sin, and that is where the modern world is wrong. It explains sin away: it ascribes it to a fall in the evolutionary process, to a survival of ancient taboos; it identifies it with psychological verbiage. In a word, the modern world denies sin. Our Lord reminds us that it is the most terrible of all realities. Otherwise why does it give Sinlessness a cross? Why does it shed innocent blood? Why does it have such awful associations: blindness, compromise, cowardice, hatred, and cruelty? Why does it now lift itself out of the realm of the impersonal and assert itself as personal by nailing Innocence to a gibbet? An abstraction cannot do that. But sinful man can.

Hence He, who loved men unto death, allowed sin to wreak its vengeance upon Him, in order that they might forever understand its horror as the crucifixion of Him who loved them most. There is no denial of sin here and yet, with all its horror, the Victim forgives. In that one and the same event, there is the sign of sin’s utter depravity and the seal of divine forgiveness. From that point on, no man can look upon a crucifix and say that sin is not serious, nor can he ever say that it cannot be forgiven. By the way He suffered, He revealed the reality of sin; by the way He bore it, He shows His mercy toward the sinner. It is the Victim who has suffered that forgives: and in that combination of a Victim so humanly beautiful, so divinely loving, so wholly innocent, does one find a Great Crime and a Greater Forgiveness.

Under the shelter of the Blood of Christ the worst sinners may take their stand; for there is a power in that Blood to turn back the tides of vengeance which threaten to drown the world. The world will give you sin explained away, but only on Calvary do you experience the divine contradiction of sin forgiven. On the Cross supreme self-giving and divine love transforms sin’s worst act in the noblest deed and sweetest prayer the world has ever seen or heard, the Confiteor of Christ: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

That word “Forgive,” which rang out from the Cross that day when sin rose to its full strength and then fell defeated by Love, did not die with its echo. Not long before that same merciful Savior had taken means to prolong forgiveness through space and time, even to the consummation of the world. Gathering the nucleus of His Church round about Him, He said to His Apostles: “Whose sins you shall forgive, they are forgiven.”

Somewhere in the world today then, the successors of the Apostles have the power to forgive. It is not for us to ask: But how can man forgive sins?-for man cannot forgive sins. But God can forgive sins through man, for is not that the way God forgave His executioners on the cross, namely through the instrumentality of His human nature? Why then is it not reasonable to expect Him still to forgive sins through other human natures to whom He gave that power? And where find those human natures? You know the story of the box which was long ignored and even ridiculed as worthless; and one day it was opened and found to contain the great heart of a giant.

In every Catholic Church that box exists. We call it the confessional box. It is ignored and ridiculed by many, but in it is to be found the Sacred Heart of the forgiving Christ forgiving sinners through the uplifted hand of His priest as He once forgave through His own uplifted hands on the Cross. There is only one forgiveness-the Forgiveness of God. There is only one “Forgive”-the “Forgive” of an eternal Divine Act in which we come in contact at various moments of time.

As the air is always filled with symphony and speech, but we do not hear it unless we tune it in on our radios, so neither do souls feel the joy of that eternal and divine “Forgive” unless they are attuned to it in time; and the confessional box is the place where we tune in to that cry from the Cross. Would to God that our modern mind instead of denying the guilt, would look to the Cross,

admit its guilt, and seek forgiveness; would that those who have uneasy consciences that worry them in the light, and haunt them in the darkness, would seek relief, not on the plane of medicine but on the plane of Divine Justice; would that they who tell the dark secrets of their minds, would do so not for the sake of sublimation, but for the sake of purgation; would that those poor mortals who shed tears in silence would find an absolving hand to wipe them away.

Must it be forever true that the greatest tragedy of life is not what happens to souls, but rather what souls miss. And what greater tragedy is there than to miss the peace of sin forgiven? The Confiteor is at the foot of the altar our cry of unworthiness: the Confiteor from the Cross is our hope of pardon and absolution. The wounds of the Savior were terrible, but the worst wound of all would be to be unmindful that we caused it all. The Confiteor can save us from that, for it is an admission that there is something to be forgiven-and more than we shall ever know.

There is a story told of a nun who was one day dusting a small image of our Blessed Lord in the chapel. In the course of her duty, she let it slip to the floor. She picked it up undamaged, she kissed it, and put it back again in its place, saying, “If you had never fallen, you never would have received that.” I wonder if our Blessed Lord does not feel the same way about us, for if we had never sinned, we never could call Him “Savior.”